News

A Look Inside Poly Upper School: Chemistry Lab with Matthew Sagotsky

“I encourage my students to work together as asking questions and running investigations to find answers mimics the practice of science.” – Matthew Sagotsky

Chemistry focuses on molecular behavior in the physical setting and learning to investigate is at the core of Matthew Sagotsky’s chemistry course for Grade 10 students. He encourages students to think like scientists, Sagotsky says, as they learn new concepts or techniques. They then apply their knowledge through hands-on experience in the lab, where they sharpen both independent and collaborative problem-solving, as well as critical thinking skills.

Lab work is an integral part of the course. Each experiment is carefully chosen to offer an active illustration of a particular concept or technique so that students can visualize and understand the physical world more clearly. Topics include: atomic structure, periodic properties, molecular bonding, chemical reactions (including stoichiometry), acid-base reactions and thermodynamics.

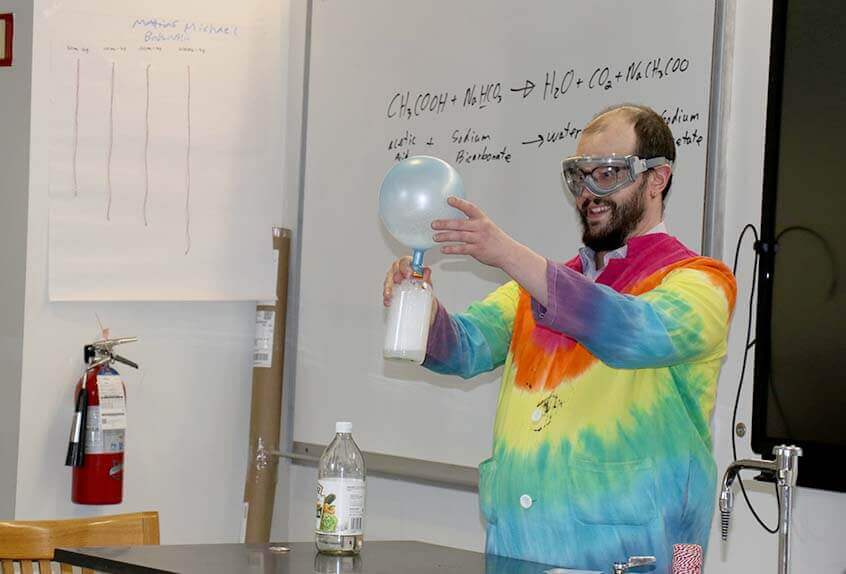

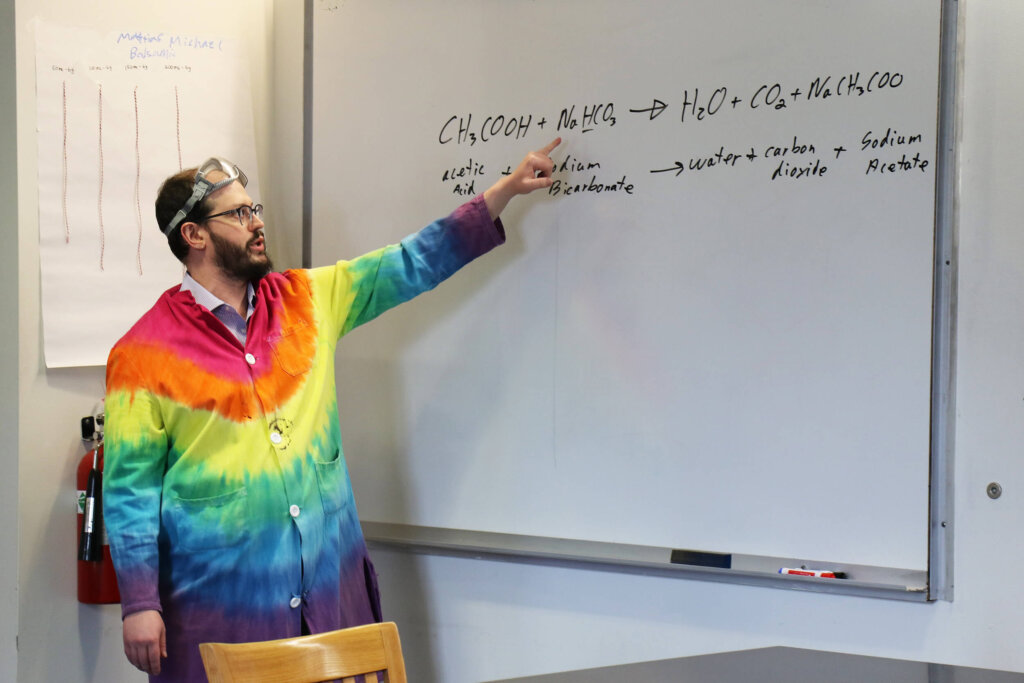

In late February, the class participated in an exciting inquiry lab where the students conducted a ‘balloon race’ by mixing vinegar and sodium bicarbonate. They filled a balloon with the CO2 released from the reaction which when measured with a string, gives a visual indication of how much products were produced. They then used their strings to make an artifact, a graph that they need to use to explain how limiting and excess reagents function.

The Challenge

The lesson-level question for the lab and engineering challenge was, “Does adding more of a reactant always produce more products?”

The activity gives students a hands-on, visceral approach to answering that question. It introduces the concept of there being a limiting (the reactant you run out of limits the amount of products formed) and excess (the one leftover) reactant. Chemistry curricula traditionally approach in a purely algebraic sense, Sagotsky shares, but it is his belief that if students can use their own data to answer this question in a written and/or verbal form then they will have the framework to quantitatively address this concept in the challenges that lie ahead.

From the beginning of the school year, Sagotsky’s classes have completed several fascinating assignments, such as storylining using the northern lights and diamonds as phenomena to drive student inquiry. Each unit begins with investigation based on a student-generated question such that the students understand the context and coherence of each lesson into the next. In fact, learning how to pose good questions is a skill itself. The class spent a substantial amount of time (especially at the beginning of the year) practicing asking good questions. “I encourage my students to work (and struggle) together as asking questions and running investigations to find answers mimics the practice of science. I expect a lot from my students. Hopefully I help them feel empowered to both own and appreciate their well-earned endeavors,” Sagotsky said.

Embracing Curiosity

By year’s end, students will have not only built a strong foundation in chemistry but also honed their ability to think like scientists—asking thoughtful questions, investigating complex phenomena, making predictions by utilizing the periodic table, and making connections between concepts. Through hands-on experiments and collaborative problem-solving, they develop the skills to analyze chemical interactions, apply mathematical reasoning to reactions, and explore the role of energy in matter. More importantly, they have learned to embrace curiosity and persistence, gaining the confidence to tackle scientific challenges with a sense of ownership and discovery.