News

Senior Philosophy Seminar Sparks Questions About Identity

The new Grade 12 Senior Philosophy Seminar being offered this fall “invites students to think about the enduring question of what it means to live well,” explained Maggie Moslander, History Department Chair, and one of the three teachers, along with John Rankin and Anthony Gini, teaching the class.

The new required course is part of Poly’s Institute for Ethics & Leadership (IfEL) initiative. “The seminar’s direct relationship to IfEL is twofold,” explained Rankin, “specifically, there are areas of philosophy that address ethics: how one decides on right action, the good choices; and more generally the class fosters analytic thinking and thereby shapes decision-making.”

“This course had as a guiding principle from the beginning—that it should be designed to help students think through big ideas in a way that connects to their lived experience.”

“This course had as a guiding principle from the beginning—that it should be designed to help students think through big ideas in a way that connects to their lived experience,” said Moslander. “We’re asking students to read challenging texts and confront difficult questions of identity, community, faith, and knowledge, while making sure that we’re constantly challenging ourselves to provide texts that represent the diverse community we have at Poly and the world they’ll enter when they leave us in June.”

“We use psychology, cultural studies, literature, and historical frames to challenge assumptions and bolster belief. It is critical, higher-order thinking that we aim to sharpen.”

“We are striving for something that brings meta-cognitive and theoretical awareness to disciplines that students have been pursuing for years,” Rankin said. “A certain history of philosophy is the course’s fulcrum, but it is not the only field of inquiry. We use psychology, cultural studies, literature, and historical frames to challenge assumptions and bolster belief. It is critical, higher-order thinking that we aim to sharpen.”

“The course we are offering looks at the traditional philosophical problems like those of metaphysics and epistemology,” said Gini, “but seeks to steer the discussions around these questions toward the goal of diversity and social justice.”

Moslander worked with Rankin and Gini to develop a course that took as its foundational text Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Lies that Bind. “I think John, Tony, and I are all bringing different areas of expertise within the discipline of philosophy,” said Moslander, “and because my background is in political philosophy, I’m excited about that unit!”

Moslander added, “We expect students to read closely, analyze critically, and write thoughtfully about enduring questions in the discipline of philosophy. And crucial to that work is the student’s contribution to class seminars; it’s only through discussing these texts that we can start to untangle them in ways that make them more accessible.”

“Most of our readings are in the essay form and the writing is a series of analytic essays of approximately 1,000 words,” said Rankin, “in the style and substance of what students can expect to see next year in college. I am personally excited to teach this course.”

“Questions of diversity, inclusion, and equity all play a role in the history of thought.”

“It was very straightforward to dovetail philosophy with IfEL’s diversity cornerstone,” Gini said.

“Questions of diversity, inclusion, and equity all play a role in the history of thought,” Rankin added. “Some of the greatest problems in philosophy emerged with the faulty assumption that universal value, common understanding, and general reason applied only to a certain privileged few, primarily of the white male variety. In studying specific writers who tackled difference, as well as carefully examining the Enlightenment’s belief in a universal reason, we hope to shed light on our benighted polarizing moment.”

Gini continued, “A student in philosophy is asked to put aside his or her preconceptions when faced with a challenging question—especially questions which have puzzled thinkers through the ages. Instead of answering from a particular perspective, a student comes to inquire what creates an epistemological perspective to begin with, and to ask whether they can find ways to critique it.”

“I always questioned identity, not only for myself, but also for others and how they used or did not use parts of their identity to mask parts of themselves.”

Isaac Blacklow ‘21 is one of the students in the first Senior Philosophy Seminar. Early in the course, the class studied identity. “I always questioned identity,” he said, “not only for myself, but also for others and how they used or did not use parts of their identity to mask parts of themselves.” He said he enjoyed having a class dedicated to the study of philosophy “instead of just having hints of it in history and English.” Blacklow said having the class outside in a tent is not a problem because, “I don’t think where philosophy is taught matters at all as it transcends the need for a board [to write on]; it is mostly a listening, talking, and thinking activity.”

“I knew very little about philosophy before taking this course,” said Ella Barnett ’21. “I feel like we have all heard philosophical questions throughout our lives, such as ‘who am I’ or ‘what is the meaning of life,’ but I had never really dedicated time to looking for any type of answer.”

“I find it so intriguing to learn the thoughts of those around me and see how those new perspectives can change the way that I view the world.”

“My main goal for the class is to engage in deeper conversations with my peers,” Barnett said. “Although so much of this work is personal in finding your own beliefs, I find it so intriguing to learn the thoughts of those around me and see how those new perspectives can change the way that I view the world. My main interest lies in the idea of identity and how it affects not only my view of myself, but also how others see me. After finishing the summer reading, I started to look into ‘the I and the me’ ideology originated by George Herbert Mead. This work that we are doing in class has made me think so much even when I am not doing school work.”

“It has definitely been interesting having this course outdoors,” Barnett continued. “Dr. Gini shows us lots of videos and images to give more context to our discussions, but that has been limited by our access to WiFi and shared screens in the backfields. Still, we are making it work as a class. Overall, being in person still encourages a lot more talking than a solely virtual class could.”

In preparing for the course, Gini said, “I am most excited about teaching pure, raw ideas, presented clearly and as colloquially, so that students feel that they can make an immediate and deep connection with them. Without having to master any specialized or technical procedures, they can arrive at deep truths about the way things hang together.”

“Someone,” Rankin said, “somewhere did an examination of why philosophy was not taught in secondary schools and concluded that the problem lay not with students, who too often feel undernourished for inspiring thought. We humbly hope to feed the hunger with a trough of ideas.”

“It is through a self-examination of deeply held attitudes and assumptions that new possibilities emerge, where hope itself becomes more tenable.”

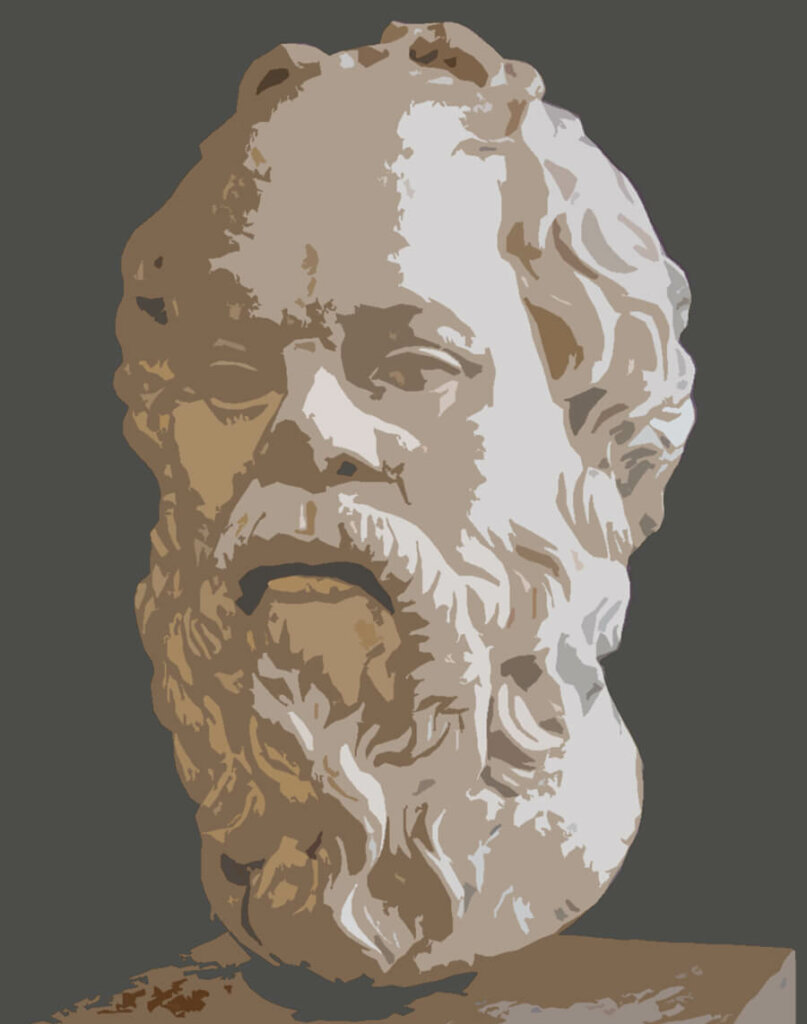

“But I can say, Rankin continued, “that 2,400 years ago the itinerant street provocateur Socrates thought that in a time of crisis the place to start looking for answers was in one’s own beliefs. It is through a self-examination of deeply held attitudes and assumptions that new possibilities emerge, where hope itself becomes more tenable.”

“… if our students can be countercultural in their embrace of complexity and nuance, I think that will contribute to both their and our country’s wellness in meaningful and lasting ways.”

Moslander concluded, “I think one of the things I hope students take away from this class is an understanding that so many deep questions about the human experience have endured over time because they are complex, and that complexity isn’t something to be afraid of. I think so often in our country today, we see people trying to reduce complex problems and big ideas to sound bites, and if our students can be countercultural in their embrace of complexity and nuance, I think that will contribute to both their and our country’s wellness in meaningful and lasting ways.”