News

After one week back from Winter Break—and with new hyper-virulent strains of the COVID-19 virus surfacing—Poly Prep continues to be innovative in its approach to keeping our community safe. Following the switch to distance learning almost one year ago, we began school in September by welcoming over 1,000 students in Nursery through Grade 12 back to our two campuses. Keeping our students in school requires constant evaluation and evolution of our safety practices.

At Poly Prep, our Health and Safety team guides us through a staggering number of questions: How many students can return? How will they get to school? Do we gate test or not? Which kind of test? Will classes be indoors or outside? Will windows be open? Do we require surveillance testing? How will we serve and eat lunch?

Schools across the city and globe have demonstrated wide-ranging approaches in tackling these questions. In addition to the outdoor tented classrooms that housed our fall Dyker Heights courses, we implemented one of the most aggressive COVID-19 testing strategies in the country. Our plan included regular polymerase chain reaction-based (PCR) testing of asymptomatic community members; PCR tests are considered the gold standard of testing in accuracy. They are nearly flawless in terms of false positives or false negatives—in theory, they are perfect for protecting institutions. But when do these “perfect tests” fall short?

Fall Testing Strategy: PCR in Practice

In our first months of PCR testing, we required an individual PCR test after each extended break, but at $50-$100 per test, ramping up our testing frequency was prohibitively expensive: the first PCR hurdle. We addressed this key problem by using a pooled testing strategy on a weekly basis. Pooling individual samples sacrifices some test sensitivity for the ability to test the entire batch at once, which dramatically reduces cost. With virus penetration rates low in New York City during the fall, most of these pooled batches turned out to be fully negative. When a batch produced a positive result, our test provider would run reflex tests, meaning that they would test smaller groups within the positive pool until we identified the specific positive individual.

From September through December, we became better at implementing our testing protocols, and we continued to test larger and larger groups each week. On Mondays, we collected saliva samples in the mornings and transported them to our contracted lab. The PCR test itself requires dozens of cycles to be run on each sample in a high-complexity reference laboratory using a molecular testing process called reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). This process takes approximately seven hours on the fastest commercially available machines. Hence, we would receive test results approximately one day after collecting samples. When labs across the city became slower as COVID-19 rates increased, the delay could extend to 48 hours. This second PCR hurdle, delayed results, means we would have school for a full day or more after collecting samples and not know if we had positives in the community.

The Data: Understanding Our Community Positives

From our own data, we learned that older students were more likely to test positive than younger students; that staff were more likely to test positive than teaching faculty; and that males were overwhelmingly more likely to test positive than females. But no lesson learned was more powerful than our contact tracing lesson, that the true cost of a positive case was not limited to the mandatory quarantining of the individual who tested positive. A single student who tested positive would force the quarantine of dozens of others—classmates, fellow bus riders, siblings, carpods, teachers, advisors, lunch supervisors, and any after-school activity exposures.

Adding Antigen (Rapid) Tests to the Strategy

With new strains of coronavirus that are estimated to be 50-70% more transmissible than the previous strain, the presence of any one case, undetected for 24-48 hours, challenges our ability to keep our campuses open. Antigen tests (also called rapid tests) are one alternative to PCR tests. In the first part of this year, we used antigen tests in small numbers, having received the necessary limited lab license to administer them. Antigen tests are less expensive, less cumbersome, much faster, and arguably not as accurate as PCR tests.

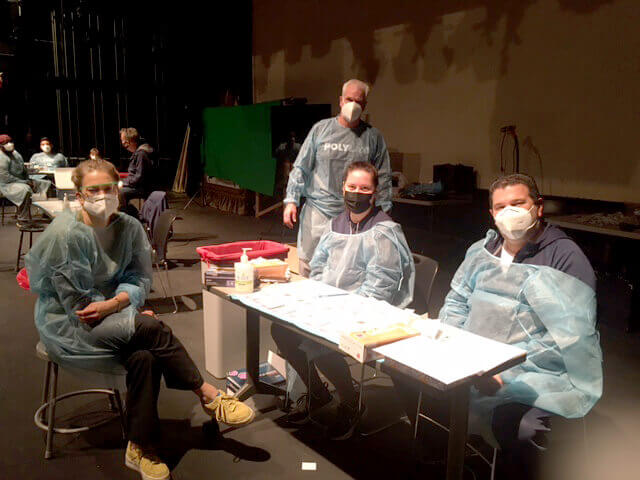

Dr. Michael Mina of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is a vocal and well-respected proponent of using rapid antigen testing on a regular basis. Antigen tests produce a result in less than 15 minutes and can be administered at a fraction of the cost of a PCR test. Our process is to nasally swab a large portion of our community weekly, with the goal to test as many as possible on Mondays before school starts. When their tests are cleared as negative, they are able to participate in school on campus. If they are positive, they will immediately be sampled for a PCR test on or off site. This reduces both the exposure on campus during the school day and the contact tracing burden. We are rapid testing all adults on both campuses at least once per week, as well as the two high school grades, 9 and 10, who attend school on alternating weeks. We will continue to transition away from weekly PCR testing and towards weekly rapid testing for as many students and employees in our population as possible.

PCR Tests v. Antigen (Rapid) Tests

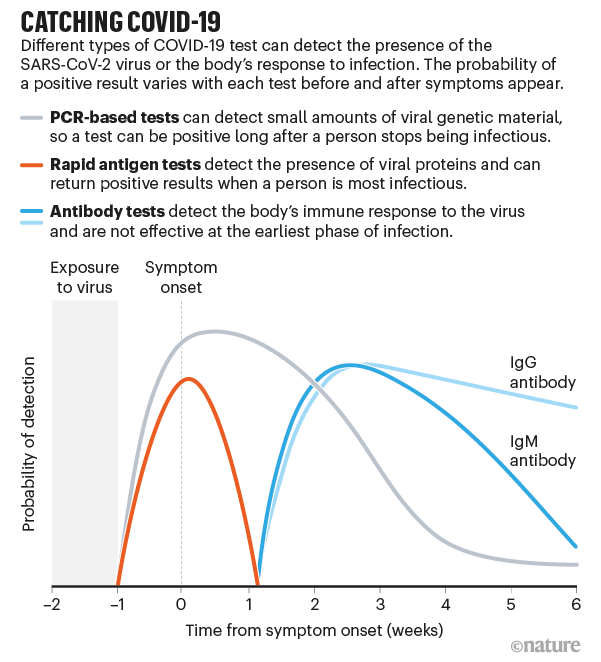

A PCR test aims to detect viral genetic material directly, it does not aim to detect infectiousness. Someone who contracts COVID-19 is only infectious some of the time after infection, which means that a PCR test positive is often not a confirmation of infectiousness. The infectious period begins approximately two to three days after infection, lasts through the remainder of incubation (defined as the period prior to the onset of first symptoms) and usually ends a week later for a total of approximately two weeks or less. Antigen tests are often misunderstood and misrepresented. Antigen tests are much better indicators of infectiousness than the more technically accurate PCR tests because they detect the presence of viral proteins known as antigens, which are generally present while infected people are actually infectious (or, at least, when most infectious). Heretofore, antigen tests have often been incorrectly benchmarked against PCR tests throughout all stages of infection—thereby comparing antigen tests to PCR outside of their intended use. More recent research focused on comparisons throughout the infectious period, which is the most important period for infection control purposes, has found that antigen tests are nearly as accurate as PCR tests, as illustrated by the graphic.

As shown, antigen tests make for ideal “infectiousness tests” and indicate most accurately whether someone is still within their approximately two-week infectious phase. PCR tests are more accurate throughout the entire infection lifecycle, which can last four-six weeks, whether the individual is infectious or not.

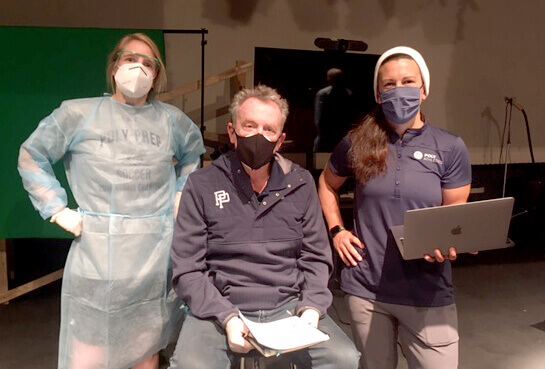

Training our Team for Results On-Site

Of critical importance, antigen tests can be administered on-site by any trained person, while PCR tests require shipment to a third-party lab with highly trained professionals required to run the tests and interpret the results. Currently, there are 11 members of the Poly Prep Health Team who have been trained to swab for a rapid test and 12 more who have been trained in assisting with the process and interpreting and recording the results.

Dr. Mina has clarified the best uses for different tests. For more information about his research and guidance, we recommend the following articles:

- Rapid Tests for COVID-19 – Open Schools and Save Lives

- Frequent, rapid testing could cripple COVID-19 within weeks, study shows

- Coronavirus: Press Conference with Michael Mina, 11/18/20

- Coronavirus: Press Conference with Michael Mina, 11/20/20

- How to Fix COVID-19 Testing: At Home Daily Quick Tests

We believe that the combination of gate testing via PCR with individual swab collection, when time allows (i.e., after school breaks) and weekly or more frequent testing via antigen tests, provides the most comprehensive solution possible to our community given today’s technology and clinical realities.

If you’d like to speak directly with someone from Poly about how our COVID-19 strategy allowed our students and faculty to return to and remain safely in school, please contact our Communications Office.

Read more about how Poly successfully continued the business of teaching and learning, while keeping our community safe during COVID-19: