News

Poly on Film Features Academy Award Winner Aaron Matthews ’89

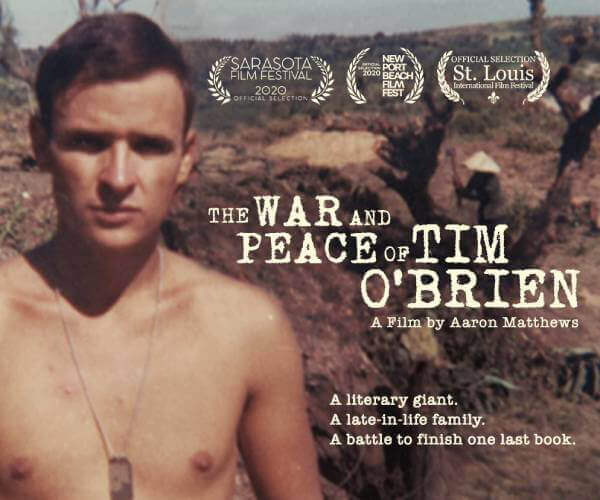

The documentary The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien, directed by Aaron Matthews ‘89, was the focus of the fifth in a series of Poly on Film events, a free discussion series featuring alumni working in the field of film and television. In 2021, Matthews won an Academy Award as co-producer of Colette, which earned the Oscar in the Best Short Documentary category.

The documentary focuses on Tim O’Brien, author of the Vietnam era memoir, The Things They Carried and Going After Cacciato, which won the National Book Award, as he tries to write his first book in 15 years, while also playing an active role in the lives of his two young sons.

The April 21 webinar panel was moderated by Robert Aberlin ’62, Director of Arts Outreach and included Stellene Volandes ’89, Editor in Chief of Town and Country, Elijah Sivin, Poly History faculty, and Christy Hutchcraft, Creative Writing teacher.

Matthews’ films have appeared on national and international television, and at over 50 film festivals around the world. His documentaries include, The Paper, A Panther in Africa, and My American Girls, all broadcast on PBS’s flagship documentary series POV, or Independent Lens.

Aberlin began the evening by asking Matthews how he had gotten O’Brien to sit down with him and make himself accessible for filming over the course of five years.

“I wore him down over time,” Matthews said. It was a year and a half after meeting him that O’Brien agreed to have Matthews come with his camera to his Austin, TX home. Matthews said they developed a friendship first. “He made me aware and alert to issues.”

“I met Tim in December 2014,” Matthews said in advance of the panel, “while working on a PBS documentary called The Draft, which looked at the history of military conscription in America. A few minutes into my interview with Tim, I started dreaming about doing a documentary on him. He’s relatable and poetic about all the subjects that move our hearts, from war and marriage to love and death. But he’s also unusual. I remember eyeing the guillotine that was four feet from me during that first interview, an artifact from one of the giant magic shows he stages. Then he told me a story about getting kicked out of a casino for counting cards, and he was chain smoking, so there was a cinematic haze to the frame. When I learned that he had two young boys, and would be spending the next few years juggling being an older father with struggling to write ‘one last book,’ I thought, ‘here’s the stuff of a good movie.’ Stories about people doing something really hard are interesting. Plus, it was an opportunity to remove the layers of mystery and prestige surrounding artists. We tend to want artists to be these unencumbered geniuses with no families, no money worries, etc. O’Brien is encumbered. A lot of people can relate. So, I trusted that if I followed Tim and his family around with a camera, a compelling story would emerge. And it did.”

Stellene Volandes ’89, who reviewed the film in Town and Country, said that Matthews “chronicles both the existential angst and the daily struggles (see: the credit card scene at the gas station) that follow O’Brien, Vietnam veteran and the legendary author of The Things They Carried, as he attempts to finish his next book, one he believes might be his last—and the one that will become the legacy of himself he leaves for his two young sons.” She said she easily could have predicted that her Poly classmate would become a filmmaker. “Aaron was a classic scholar-athlete,” she recalled, who had already read all the books before they were assigned for class.

Aberlin noted the recent Ken Burns documentary about Ernest Hemingway, observing, “Writers and writing don’t necessarily lend themselves to film. You found a way to.”

Matthews acknowledged that “a writer could be dull sitting around in his underwear writing,” but that “Tim has a kinetic energy, a freshness of words, and a twinkle in the eye.” He added that O’Brien is “unfiltered” and has a “level of candor” that many people do not have.

“I shouldn’t have been surprised by how much overlap there is between telling a good story on the page and on the screen,” Matthews said in advance, “but learning the extent of that overlap, while being with Tim as he struggled to create good sentences, was a pleasant surprise. Things like: Exposition kills your story; trust your audience to understand your themes; leave room for audiences to bring their own experiences to the material; a scene that is rigidly about one thing is in danger of being a polemic, and boring. And this: the idea that you have to discover your story as you create it, that in writing and filmmaking you’re stumbling along until you find the perfect thing, that you need to create a space for the astounding to happen. These were some of the many storytelling principles I talked extensively with Tim about, and getting to share these principles and see the intersection between writing and filmmaking was exhilarating actually.”

Aberlin asked Sivin to recall Matthews from when they were in elementary school together. Matthews, he said, was “one of the funny kids,” while Matthews remembers Sivin as a “smarty pants.”

Christy Hutchcraft said, “Tim O’Brien has been a revelation to me.” Like O’Brien, Hutchcraft’s father was drafted to serve in the Vietnam War. “O’Brien put a face on something about my father” that she had desired to know more about.

Aberlin asked Head of Technology Charles Polizano P’18 to show a video clip of Tim with his sons. The boys said about their father, “his mood depends on whether he has good or bad writing days.” Aberlin asked Matthews how he got the sons to be so open with their comments. Matthews explained that he was not intrusive, using only one camera. Indeed, O’Brien told him that his favorite scene in the film was with his sons because “he learned the most about himself and his family.”

Matthews said that the film shows the “pain of writing,” the “torture of the creative process.”

In another clip, O’Brien is leafing through an envelope of scraps of paper on which he has written ideas for chapters of his book. He describes them as “fireflies that shoot through my thoughts.”

Hutchcraft said the scene “captures the messiness of writing.” O’Brien, when he is stuck in the messiness and has writer’s block, literally gets down on the kitchen floor to scrub it. Sometimes, “messy” can be a good thing, Hutchcraft said.

Aberlin asked Matthews how he organized over 100 hours of film and condensed it into an hour and a half. “Every story is different,” he explained and sometimes there is organization to what seems a mess. “The thing you are looking for leads you to the thing you weren’t looking for,” he said.

In another video clip, O’Brien is reading to his kids. “He was essentially taking time away from his family so that he could give his family a memento after he died,” Matthews recalled. “That struck me a lot, especially since I was spending a lot of time away from my own family in order to make this film. It’s a dilemma most of us find ourselves in with regard to work and family — we spend all this time away from the people we love so that we can support and spend more time with the people we love.”

Aberlin invited the audience to ask questions in the Q&A feature, which was moderated by Head of Arts Michael Robinson. In response to a question about O’Brien and the trauma of war, Matthews said O’Brien saw “struggling as part of living” and that O’Brien was “very open about his own trauma. In bed every night, O’Brien imagines himself falling asleep in the safety of a bunker, Matthews said.

Someone else asked about O’Brien’s ever-present baseball cap and Matthews explained, “Tiim owns a ton of hats” and his casual dress has become a different kind of “uniform.”

In another clip, O’Brien notes that he is known as a “war writer” and will be “remembered for the thing that most haunted me.” Matthews said O’Brien takes pride in his books and that many veterans find them relatable. Sivin observed that O’Brien is tough on himself and pessimistic even in his peace activism. Matthews said that in one part of The Things They Carried, the character, who might have thought about dodging the draft, says, “I was a coward. I went to war.”

What would Matthews like the viewer to take away about O’Brien? “That he’s fiercely honest about the nation and himself,” Matthews said, “And he maintains a sense of humor about it. For that reason, he’s one of the few artists who’s real, honest, and open enough to let us witness his struggles. Especially in turbulent times like the ones we’re living in now, Tim makes for a good companion. Everyone wants to know they’re not alone in their struggles, and I hope they find some level of comfort in seeing Tim, who’s had various struggles in his life, if not completely emerge from these struggles, figure out how to live with them. Tim recognizes the value of struggle — that to live is to struggle, because struggling means you care. So it is not something we should avoid, but rather pay attention to, and nourish.”

“Also,” Matthews said, “I hope viewers reconsider America’s long fraught relationship to war and the military. Tim is wrestling with something we all should be wrestling with: what it means to live in a highly militarized nation, engaged in military action around the world, with a culture and politics that revolve around WAR.”

In the final clip that Aberlin shared, Aberlin said that Tim O’Brien summarizes the film in words to his sons: “It’s hopeless, but pretend it’s not.”