News

By Polygon Staff

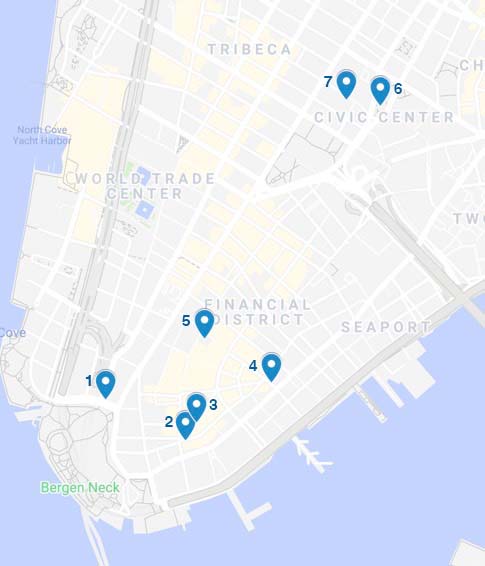

In one of Poly’s newest history elective classes, Slavery and Resistance, Dr. Alex Carter’s students took a field trip last month to Lower Manhattan to explore the significant history and impact of slavery within and outside of New York City as part of the NYC Slavery and Underground Railroad Tour. The goal of the tour was to understand the centrality of slavery to the city. Furthermore, the class works to push back against the idea that slavery was a “southern thing” and develop a more profound knowledge of the resistance strategies that free and enslaved people utilized to survive and exert their humanity against a system that deemed them “property.”

Note: This feature story was originally published in the Polygon’s November 2021 print edition as one of three topical articles that also included How New York City Has Pushed Away its Slave-Centered History by Terrel Hood-Simon and The Legacy of Enslavement in New York City by Lizzie Torigian-Gini.

Below is a series of reflections from members of the class on each of the stops:

Stop 1: The Netherland Monument

The Dutch Monument that commemorates the establishment of New Amsterdam was a representation of the relationship between the Dutch and the Lenape people. It was a false advertisement because it claims that New Amsterdam was sold for $1,000 to the Dutch. —Sammy Agate ’23

The tour’s first stop was a monument depicting the Dutch buying New York’s land from the Lenape people. However, this depiction is utterly false to what happened. — Carlo Caffuzzi ’23

It is believed that the exchange of gifts was a sign of greetings for the Lenape people, whereas the Dutch denoted it (as does the monument) as if they “purchased” the land. The Dutch did not “purchase” the land since that concept or private ownership of land was not a mode of thinking for the indigenous people of Manhattan. — Dr. Alex Carter

Stop 2: Fraunces Tavern

The Fraunces Tavern is a tavern that dates back to the 18th century. It is most famously known for serving as George Washington’s headquarters/meeting place. The tavern was initially owned by a man named Samuel Fraunces. It has been debated whether or not Samuel Fraunces was a black or a white man. The Tavern was a site of Underground Railroad activity. —Thomas Collier ’23

Stop 3: The Philipse Manor Well

This specific well was on the Philipse family’s property. This particular family happened to be one of the largest enslavers in all of New York, New Amsterdam at the time. This well is significant because, although it was used during labor, it served as a sense of resistance and community building among enslaved people. The bonds and community formed at this well were the building blocks of a community, which eventually led to freedom. —Ariana Dicarlo ’23

Stop 4: The site of the First Municipal Slave Market in NYC

At [New York’s first municipal slave market] site, we learned that NYC banks such as J.P. Morgan and Chase made enslavement possible and that slaveholders would come all the way to New York from all around the country to buy enslaved people. I had also never known how the municipal slave markets would be places that enslaved people would be leased for short periods of time. The site of the first municipal slave market in NYC was really fascinating to me because often the role that all northern states—especially New York—played in enslavement goes unrecognized. —Hayden Lewis ’23

Stop 5: The former site of Thomas Downing Oyster House

Thomas Downing Oyster House represented a significant moment in the Underground Railroad as a free Black man risked imprisonment, fine, and potential enslavement to help self-liberated people fleeing to points North of NYC. We were reminded that even free Black people could be accused of being a “runaway” and sold into enslavement. Frederick Douglass made the Oyster House home briefly during his flight to Massachusetts. —Bella Nash ’23

Stop 6: Foley Square

The executions that took place at Foley Square were related to the slave revolt that occurred in 1741. Thirty-five people were convicted for this revolt and were assumed to have set fires to the houses of white people. The only commemoration of the deaths of those convicted is a monument with a small and fading plaque and a depiction of the events on the ground. —Sid Rothkin ’23

I was shocked that the circular plaque commemorating the site was so small and on the ground. People literally walk all over it every day. They were filming Law & Order SVU there as well, so I wondered how many cast and crew members knew the horrific past of the square they’re filming on. The whole tour really opened my eyes, as I just now learned how much New York City was built off of slavery. —Lizzie Torigian-Gini ’23

Stop 7: African Burial Ground National Monument

In 1697, the church declared that enslaved people must be buried beyond the wall (Wall Street), so this burial site was created. When construction for an office building took place in the area, 419 people’s bodies were found. The site became the largest African Burial Ground in the United States before being forgotten about—anthropologists estimate that more than 15,000 people are buried there. Though it was upsetting, I believe it is essential to make sure we don’t forget that those who were enslaved are people who deserve to have their stories remembered and that we shouldn’t insult them by ignoring the atrocities they experienced. —Keelin Walshe ’23

The African Burial Ground was a beautiful sight with a black marble stone pavilion that led into the central circle. There was writing on the ground saying the approximate age of each body they found. There were signs all around the staircase resembling African symbols of peace and continuity of life and others and seven mounds in the grass to resemble the bodies. —Ezra Zizmor ’23