News

Alumnus Shares Stories of His Life as Investigative Journalist

Imagine waiting in your car for three hours in a trailer park hoping a source will show up who can provide you with key information for your news story.

Former Polygon editor-in-chief David Gauvey Herbert ’03 returned to share such stories about his career in investigative journalism with Poly’s current Advanced Journalism students and staff of The Polygon.

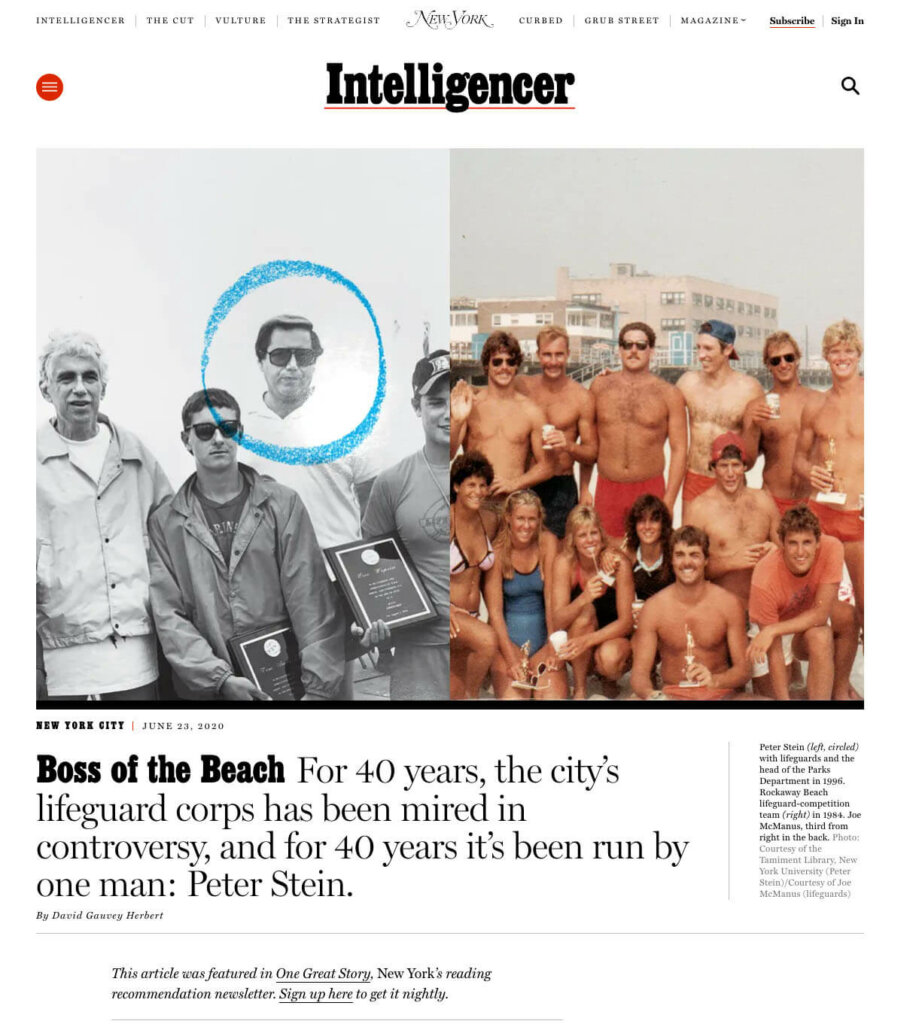

Herbert is a freelance writer who has written about crime and subcultures for New York, Esquire, and Bloomberg Businessweek. He is a two-time grant winner from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. As a professional journalist, he has investigated NYC’s controversial lifeguard corps, cults, youth baseball’s dad-on-dad rivalry, a Porta Potty king, and more.

“Boss of the Beach” & His Time at The Polygon

Advanced Journalism teacher Rachael Allen’s students had read Herbert’s piece “Boss of the Beach” for New York magazine about Peter Stein and New York City’s lifeguard corps. After introducing themselves to Herbert, the class, many of whom are Polygon staff members, settled in to listen to Herbert recall his time on The Polygon. After not being able to cajole Commons staff into serving him Beef Stroganoff with only noodles, minus the beef, he decided to write an opinion piece for the paper. Cooler heads prevailed and the op ed was toned down. But the original version ended up being laid out and was published. Fortunately the Polygon advisor went to bat for him. Ergo, “Layout is very important,” Herbert stressed to his listeners.

“I joined The Polygon in ninth grade,” Herbert said, and he was one of the students who typically stayed on until the 6:00 PM bus. This was the beginning of his journalism career, which continued on The Stanford Daily and small papers before Herbert went to Washington, D.C. to work on The Atlantic. Herbert, who lives in Brooklyn, now works as a freelance magazine writer doing three longform stories each year.

Tenacity and Patience

What Herbert really seems to enjoy is the whole process of coming up with a story idea and then doing all the legwork digging deep for the facts and detail that make his stories come to life. This might mean doggedly tracking down a potential source and then sitting in a car in a trailer park for three hours waiting for that person to show up to provide a few answers or tracking down social media or tax forms for information.

“How do you keep it all organized?” a student asked Herbert about his research process. He explained that he tries to anchor the story on a main protagonist. He explained that he uses index cards to lay out the story the way you might do for a film. His research may consist of “thousands of docs and piles of books.” His notes file can add up to a document of 35,000 words that will need to be whittled to 8,000 words for publication.

“I want it to read like a movie.”

Herbert said he has an assistant who helps him in “story generation,” but something as simple as a bike ride to the Rockaways can be the spark to ignite a story. Then Herbert is off to the races piecing together a compelling story through tireless research and investigative skills that may lead to litigation databases. “There is so much you can piece together from Instagram and Facebook,” he added. “I love the exhaustive reporting.” He told students he once flew to Florida to get a few more details from a source. Doing this can result in “more stuff than you will ever use,” he admitted, but it all adds to the detailed scenes that he creates to captivate his audience. “I want it to read like a movie.”

Herbert told the young journalists that when a source sees that a reporter is invested in the story and isn’t going to go away, that alone can “get people to go from ‘no’ to ‘yes’” as to whether they will speak with him. “Knocking on people’s doors will go a long way,” Herbert said. But in reporting on the lifeguard story and Peter Stein, Herbert said that nothing would compel Stein to speak with him.

“The idea of journalism has never been more valuable,” Herbert told the students.

Before the 4:00 PM bus departure, Herbert had time to talk to the rest of the Polygon staff in the Communications space. He recalled that when he was on the newspaper’s staff, there was no Facebook, no social media. He had to go to the back parking lot to use a payphone to call someone with questions for a story. Herbert talked with the staff about stories they are hoping to do, such as composting at Poly. He said he loved his time at Poly and made great friends. It was where his journalism career began.

Student Takeaways

Afterward, Jordan Millar ’24 said, “I would say the most useful advice he shared about becoming and being a working journalist is that you may not always find an answer to everything in your stories. There are going to be instances in which parts of a story will be unresolved, and as a journalist, you have to learn how to accept that uncertainty and make the most of it.”

“I think the most useful advice Herbert shared with me about becoming a journalist is to ‘follow the money.’” said Seanna Sankar ’24. “This was something that I hadn’t really thought about, but it could prove useful especially when you get stuck.”

“What surprised me the most,” said Thomas Iannelli ’24, “was how much research went into finding some people and information for the lifeguard story.”

Millar added, “One thing that surprised me about how he investigated and reported the lifeguard story was the fact that he didn’t actually interview Peter Stein, the story’s main subject. It was really interesting to learn that he interviewed 50 lifeguards, as well as other subjects, and could craft such a compelling story without ever talking to Peter Stein himself.”